- Home

- E. B. Duchanaud

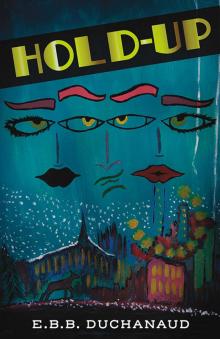

Hold-Up

Hold-Up Read online

Hold-Up

E.B.B. Duchanaud

Cover design by Jes Davis.

ISBN (Print Edition): 978-1-54396-100-3

ISBN (eBook Edition): 978-1-54396-101-0

© 2019. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

Contents

Acknowledgements

1. ALEX

2. CHARLOTTE

3. PEG

4. ALEX

5. CHARLOTTE

6. PEG

7. PEG

8. PEG

9. ALEX

10. CHARLOTTE

11. CHARLOTTE

12. ALEX

13. CHARLOTTE

14. PEG

15. ALEX

About the Author

Acknowledgements

Alex, Charlotte and Peg have been living and breathing inside me for decades and thanks to circumstances and people in my life, these characters have had the space and attention they needed to grow. From Baudelaire to Hugo to my three muses of a different rite—Charlotte, Margaux and Olivia—and, to my husband-turned-personal-editor, love has been the impetus for every word written. I do believe that we all have an Alex, a Charlotte, or a Peg living deep inside us who needs a little listening to. I may not have learned all they were telling me, but I certainly listened long and hard. Hold-up is a celebration of those inner voices full of insecurity and vulnerability and dreams. It is a testament to the importance of honoring all facets of who we are. The sparkly and tarnished. The bold and the uncertain. Because when we are whole, we can be heroes!

1. ALEX

Tuesday

The rough seat belt presses hard into my neck every time Todd twists the steering wheel and jerks on the brakes. I can feel my face turning red, the telltale sign of panic. What’s more disturbing, though, is that I’m more worried about looking freaked out than about the wheelie Todd’s about to make around the Radley Street curve in five . . . four . . . three . . . two . . . one . . . .

“Just a little grown-up fun, Freshman,” he says.

But I’m a sophomore. And after two months of driving me to and from school, Todd is well aware of this. Note to self: Alexander Hoffman, when you’re a senior, don’t rub it in some pathetic younger guy’s face. Squealing wheels and a couple of long honks get him cackling. I can totally picture flipping through the newspaper ten years from now to find a black-and-white photo of Todd in handcuffs for the murder of his coworkers or his parents or whoever gets in his way. And I’ll sit back in my Manhattan office, drinking black coffee and eating a bagel with cream cheese, and I’ll remember these hellish rides to school and think to myself, And all I cared about was not looking panicked? No, until I came along, I’m pretty sure pathetic never looked so . . . well . . . pathetic.

The snow is falling fast, but it’s like Todd hasn’t even noticed this freak blizzard in April. Without turning my head from the side window, I try to read the speedometer but I already know we’re way over the limit. My stomach just did a flip as we flew over the Beuler Street hill, and that doesn’t happen unless you’re well over thirty-five. But I know I won’t say a thing. I guess that means I’d rather have an accident and maybe die than speak up. There’s another disappointing character trait to go along with fear-of-looking-panicked: rather-die-than-speak-up.

In all fairness to myself, however, speaking up is more complicated than it might seem. It would mean finding a new ride to and from school. It would mean admitting to Todd that I’m scared. Most of all, it would mean more worry and stress for Mom, who already has enough on her plate, between trying to make partner at her law firm and Dad leaving us high and dry two months ago. Seven weeks and three days ago, to be exact. She was all bright-eyed when she told me her colleague had a son who could drive me to and from school until I got my license. Driving had been Dad’s job. That was the only time I’d seen her eyes sparkle since Dad left. No, confronting Todd is highly complicated.

Snowflakes whiz by the passenger side of the car, and I try to follow one the length of the window. It’s basically impossible, and even though I know this, and even though it makes me dizzy, it’s a way to pass the next three minutes until we reach the school parking lot. In this black leather seat, I’ve learned that anything can happen in three minutes. The four-way stop just a few bends away at Rose Avenue, Todd’s sweet spot, has taught me this. At Rose Avenue’s stop sign, Todd usually rolls semi-cautiously into the line of traffic; but on a messy day like today, when even Mother Nature isn’t following the rules, the stop sign might just translate as a license to gun it. I clutch the door handle with my right hand in preparation as we swerve ahead. Once we’re through the intersection—if we make it through—we’re thirty seconds from school, thirty seconds from safety.

Safety. That word has just recently made its way into my vocabulary. And I don’t like it. Fear too. I try to twist my head to the front and stop following snowflakes out the side window, but it’s like trying to tear your tongue from a frozen metal pole. Not possible. It’s not until you pour warm water down the pole that you can loosen it. I don’t know what the hot-water equivalent will be for me and the side window, but for the moment I’d just as soon keep my eyes on the snowflakes.

Safety. Fear. As a half-decent freestyle skateboarder, doing flip tricks, my specialty in slides and grinds, these words should never be on my radar. Ever. Hell, I was doing ollies at age four! I did some pretty big rock climbs with Dad too. Stuff most fifteen-year-olds wouldn’t dare try. Dad. There’s another thorny word. In the “Objects in mirror are closer than they appear,” I catch a glimpse of the scowl on my face. I can’t tell if Todd put it there or Dad. Damn.

“Hold on, Freshman!”

“It’s Alex.” Two words and my throat feels swollen and achy. It’s like I’m allergic to speaking. Out the side window, I see the four-way stop coming up and squeeze the door handle until my fingers ache.

“Granny isn’t gonna be happy about this.” Todd’s referring to the man in the pickup truck outside my window on the right who looks about the age of my dad—maybe forty-five. The man was at a full stop before we reached the stop sign, but as he pulls out when it’s his turn to go, Todd slams on the gas, unleashing clinking and clanking on the passenger-seat floor. I keep my head turned toward the side window and feel one of the culprits roll to my feet. It’s an empty bottle of Arizona Ale with the blue bobcat on the label. As our wheels churn through the slush and my head spins back against the headrest, I feel the thud of more bottles against my heel.

I hold my breath as we slide by Granny, who is practically doing a push-up on his horn, and it’s no wimpy horn. I twist back to watch through the back window as Granny, probably 6’2” and 200 pounds, whips out of his pickup in the middle of the intersection, his construction boots sliding in the slush. I suppose that’s my hot-water equivalent.

“You’re not going to say anything about that four-way, are you, Freshman?” Todd is able to make anything sound deviant. He screeches into a parking spot and waits for my answer.

Hell yes, you flaming jerkwad, you j-wad on steroids! Hell yes, I’m saying something! I try to make myself say these words, at least some of them. Any of them. I’m on school property now, so if he does decide to kill me, there’s no way he’ll get away with it. But I still say the opposite.

“No, I won’t s

ay anything.” Safety and fear, those traitors, are keeping me quiet. I can’t ignore the rumors about Todd almost killing a guy on the wrestling mat a couple of years back. I watch his muscles take on a life of their own as he unbuckles his seat belt. He’s so not someone I would ever tell on.

I pry myself from the car and try to work out the kinks in my shoulder without Todd noticing. My right hand is cramping up after ten minutes of clinging to the door handle. It would’ve made more sense to grab the door with my left hand too, but I try to keep that hand, the one closest to Todd, unclenched and relaxed. I can’t even utter a word to the guy, and yet I expect my left hand to tell him how cool and Zen I am. My self-esteem has just hit an all-time low and I’ve only been awake forty minutes. Not once, not ever, did I feel like this at Greenbriar Prep. If this is what public school is all about—breaking you down, crushing your spirit—then I guess I can understand why Greenbriar Prep was so expensive. When it rains, it pours. My mom is always saying that. But when it’s shit falling from the skies, it doesn’t just pour, it buries you alive.

It’s been almost three months since I left Greenbriar Prep. Since I was kicked out, I mean. Three months later and I still can’t get the images of what happened out of my head. And once those images take hold, it’s like nothing around me exists anymore. They make Todd’s muscles and reputation fade into the background; but it’s not like that’s a good thing. To be honest, I’d welcome a day careening around hairpin curves and through intersections with Todd at the wheel if it meant the flashbacks would go away.

Supposedly, your true self comes out in moments of crisis. If that’s the case—and I think it probably is—I am hit with the daily reminder via flashback that I’m a pretty shitty human being. Thanks, Dad, for the shit gene. I can feel Todd’s hot breath against the back of my neck as he follows me into the school, and I try not to inhale or get unnerved, but my cheeks are turning red. I can feel it.

“My car. Right after school. Or I leave without you, Freshman.” Todd’s voice is low, like a menacing growl. His humid breath permeates my face. And then he turns down Hall C, leaving me in a frantic haze. I walk toward my locker, but I’m no more present in these hallways than I am on Mars. Someone’s hand drops heavy on my shoulder and I flinch. When I spin around, I’m relieved to find Zefi.

“Jesus,” he says. “I’m your best friend, not the chain saw murderer.”

“I’ve lost my mojo, Zef.”

“No one from private school has mojo,” he says matter-of-factly. “I’ve got Ditman for homeroom in a couple of minutes and I haven’t done shit.” He shuffles through his notebook. “By the way, I’ve got a Lincoln Times meeting Thursday. Got any article ideas?”

“Article ideas? I’m the newbie, remember?”

“Do I sense a mojo-missing someone feeling sorry for himself?” Zef pouts his bottom lip, opens his eyes wide, and stares at me, but it isn’t funny.

I show him the red mark on my neck that I think might be bleeding a little as proof that I’m not close to laughing.

“You need a new ride to school.” He flips his pre-dread, ratty hair behind his shoulders, but as soon as he buries his head in his notebook, his hair drops like dust balls into his face. “Talk to your mom. She’ll figure something out. What about the bus?”

“I’m out of district boundaries. I’m only at Lincoln because my best friend is.” I am slightly embarrassed by how cheesy this sounds, but it’s true.

“Aw, shucks,” Zefi says. “How is it that you get expelled from prep school and then get to choose your public high school based on a best friend? I want your parents.”

“It’s called guilt, not amazing parenting.” I know I’ve told Zef all this before, but he doesn’t believe in asking a question just once.

“If it hadn’t been for Dad, I never would have gotten expelled.” God, I hate talking about Dad, but no way will I let Zefi misconstrue Dad as a good parent, and so for the gazillionth time, I let myself get roped into elaborating. “When Dad went to talk to the headmaster about reducing my three-day suspension and Wagner disagreed, Dad put up his fists to fight. Stood up nose-to-nose with Headmaster Wagner. That’s when Wagner must’ve said to himself, ‘To hell with this,’ and flat-out expelled me.”

Zefi stares quietly at me, waiting for juicy details, but there aren’t any. He should know that by now.

It’s at this moment that Todd appears at end of the hallway. He’s surrounded by his muscle-bound buddies and a couple of senior girls who look older than the average senior girl, with their makeup and big boobs and their boyfriends’ arm draped over their shoulders like it’s no big deal. And crap, that is a big deal.

“Let’s egg his ride!” Zef cups his hand around my ear and his lips, as if there’s a chance that someone in Todd’s entourage can read lips, as if someone in the Todd Posse would even bother to look in our direction.

“He’d know I did it,” I say.

“Not a chance,” Zef says. “To be a suspect in Todd’s mind would be an impossible move up the social ladder.”

“I can’t do it to my mom, asshole,” I say.

“Your mom? Your mom’s not the one in Todd’s car every morning!”

“You haven’t seen her since Dad left us, Zef.”

“Banana in the tailpipe?”

“I’m all she’s got.”

“Okay, so you’re Mommy’s Superman.” He flips open his Lincoln Times spiral. “Sure you don’t have any ideas for a newsworthy story?”

The bell rings, and I have to say I’m more than ready to get to Algebra 2/Trig, more than ready to replace thoughts of Dad and Todd with radical equations and extraneous roots. That’s how bad things are.

“One more idea,” Zefi whispers, half laughing.

But I don’t listen and walk away toward homeroom. My neck is feeling better, my throat too. Maybe I’m building something out of nothing, a mountain out of a molehill. Pretty soon I’ll be driving myself to school and Todd will be history. Maybe all I need is a little patience.

* * *

It was after school, a Friday, and because so many kids take three-day weekends at Greenbriar, the place was like a ghost town ten minutes after the bell. Ina was talking on her cell, laughing as she walked down the stairs leading from the school entrance into the lawn. I was bopping down the steps too, and because no one except Ina was around, I decided to try a grind down the railing that ran down the middle of the staircase. Even though I had been warned a gazillion times about trying stupid stunts on school property, it seemed like a harmless T.G.I.F. kind of thing to do. Those people who talk till your ears bleed about twenty-twenty hindsight and how a split second can change your life, well, I hate to admit it . . . but they’re not just talking bull to impress you or to make you feel like an idiot. If Ina had just kept on walking down the last two steps and into the lawn and not turned around, or if I had just gotten my shit-brained idea two seconds later, none of this would’ve happened. Two seconds would’ve made all the difference. Two seconds later and the skateboard would’ve sliced through the bushes behind Ina and not through her face.

I don’t remember how I lost my balance, how the skateboard flew out from under me and planted itself in her mouth. What I do remember, though, is the blood. The blood that spilled down the skateboard protruding from her face. The blood that made thick splotches all over the stairs and onto her cream-colored coat and matching hat. The blood that didn’t look real because there was so much of it. 30 Days of Night kind of thing. When I got up from my fall, I ran over to her and began trying to pull the skateboard from her mouth.

“Are you okay, Ina?” What an idiotic question. She was so obviously not okay. And even if she had wanted to answer me, she couldn’t have because of my skateboard in her mouth. She gurgled something I assumed had to do with kindly removing the board from her mouth, and so I tried.

I didn’t realize at the t

ime why it was so hard to pull out my board, but now, thanks to that spectacular twenty-twenty vision, I can see that it was because a couple of her teeth were lodged in the wood of the board. Stupid me just kept pulling like a brute until it came out, along with the two, maybe three teeth that dropped like Tic Tacs onto the concrete. She started moaning loudly, probably because she heard them fall too. And because the board was no longer wedged in her mouth, the blood began dripping like rain. Ina’s nose was so swollen that her eyes were like slits, and I remember wishing that she’d close them and stop looking at her own unraveling and leave that to me. I dabbed the arm of my sweatshirt in between her lips to try to stop the bleeding, but she screamed so loudly that I pulled it back out. Stuffing a dirty sweatshirt sleeve into Ina’s mouth, I admit now, was not one of the more sophisticated ideas I’ve had in life.

As I removed my sweatshirt sleeve from her mouth, Mr. Wright came slipping-running out of the school toward us as fast as his loafers would take him. He jerked me and my bloody sweatshirt away from Ina, and as I sat there in a daze on the steps next to them, not daring to look at Ina and her swollen, bloody face anymore but not ready to face the small crowd watching the whole scene from the lawn, I focused on the splotchy steps. And that’s when I noticed the pennies in Mr. Wright’s loafers. Now I’ve never worn loafers, wouldn’t be caught dead in loafers. I’m more of a high-top kind of guy. What I mean is that I never realized there was an actual slot for Lincoln’s head in those shoes.

In the case of Mr. Wright, both pennies were shiny and heads-up, Lincoln’s head facing him. Maybe it was the shock of it all, but for the rest of my time on the stairs, I couldn’t get the image of our plain-vanilla registrar waking up extra early every morning to choose his lucky pennies for the day. I wondered if he kept his pennies in one of those jelly jars or in a plastic Ziploc bag. If he polished them before inserting them into his shoes. Yes, as Ina was bleeding out through her mouth and nose, I wondered whether the pennies in his loafers shared the same year, and if they did, what that year signified. I imagined that if there were a common date—which I decided would be extremely creepy—it was his birth year, which got me wondering about how old he was. I’d always figured him to be about Dad’s age, but seeing him up close and personal there on the stairs, I noticed a bald spot underneath his fluffed-up red hair and sunspots on his hands, the kind my granddad has on his forehead.

Hold-Up

Hold-Up